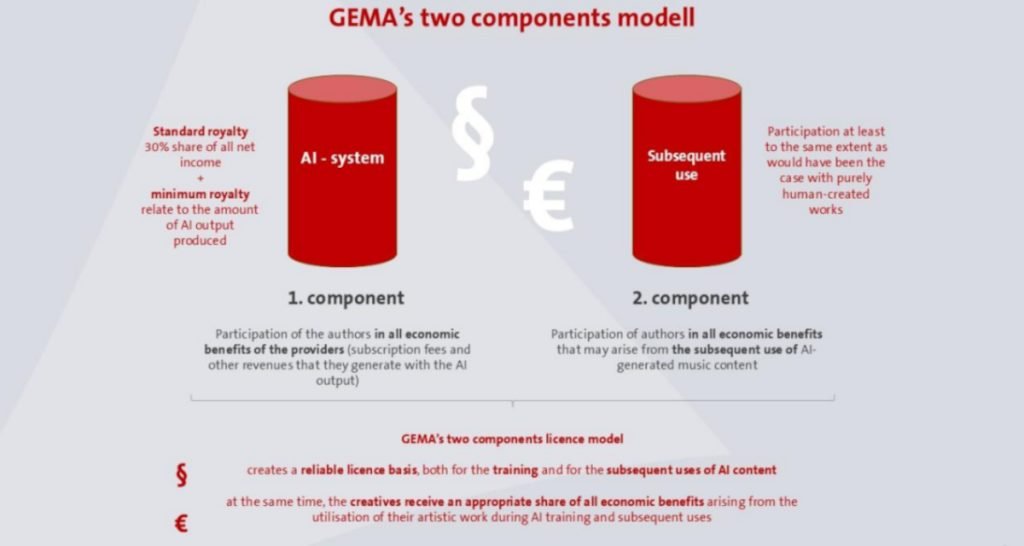

An overview of the GEMA licensing model for generative AI platforms. Photo Credit: GEMA

One month ago, GEMA announced a licensing framework for generative AI, complete with rightsholder payments for derivative audio creations. Now, the German society is providing additional details about the aggressive proposal.

GEMA reached out with new information pertaining to the model, after we asked about its specifics in late September. In more words, a representative explained the month-long response window by emphasizing the many moving parts associated with developing an approach to music licensing for generative AI.

“Involved” only begins to describe the undertaking, which GEMA touted in September as the first “licensing approach aiming to balance technological progress and the protection of creative work.”

That same month, the 91-year-old entity indicated that its model, not solely addressing once-off payments from AI developers that trained on protected music sans permission, would look to compel ongoing rightsholder payments for derivative audio creations.

As suggested by the available resources, derivative audio referred to all the music creations pumped out by generative AI platforms trained on copyrighted works without licensing pacts in place.

GEMA is now elaborating that its proposal centers on “one licensing model” featuring “two key components.”

The first of those components would apply to all generative AI players active in Germany, regardless of how, where, and when their training processes occurred, that utilized protected musical works at some point.

Far from subtle, the same component would then transfer to the relevant rightsholders “a 30% share of all net income generated by the generative AI model or system of the provider,” per GEMA, with a “minimum royalty” obligation in place to boot.

Of course, outlining the sizable payment is one thing, and actually getting AI companies to cough up is another challenge altogether. (OpenAI has already threatened to leave the EU over regulations, for instance.)

But it’s worth bearing in mind the EU’s enactment of the sweeping AI Act, which is still going into effect, and the unique regulatory environment in Germany itself. Running with these points, the second licensing component floated by GEMA will seemingly prove harder yet to make reality.

Payments should also be made for “all economic benefits that can arise from the subsequent use of AI-generated music,” including in public establishments and on streaming services, because this music resulted from an initial library of protected media, according to GEMA.

“In the future,” GEMA proceeded, “rights holders will so receive an appropriate share of the additional income generated by AI-produced songs. This share must be at least equivalent to what would have been provided for purely human-generated works.”

Though it looks as though many details still need to be ironed out – plus, the language barrier certainly isn’t helping given the highly complex subject at hand – it’ll be interesting to monitor GEMA’s push as well as the wider area of possible regulation on the AI-training side.

Meanwhile, high-stakes litigation is still plodding along in the space, with ongoing copyright cases against Anthropic, Suno, Perplexity, and Udio, to name a few.